Lore, Libel & Lies

A note to my Chatfield kin from me in 2003:

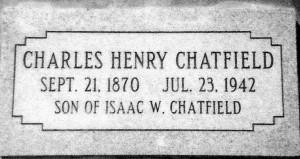

A few months back my brother Gordon, his wife Marian, and my sister Liz drove with me to Chico, Colusa, Marysville, Princeton, Columbia and Sonora for Chatfield family research and history. We haunted city halls, county buildings, family homes and work places, went to swimming holes, train stations, levees and museums, stalked libraries, schools, churches and cemeteries. We found our grandfather’s (Charles Henry Chatfield) unmarked grave. Gordon and I bought him a headstone. Had I known then about the cobalt blue Bromo-Seltzer bottles, I would have also erected a couple of those for a little color. Instead—and as it didn’t cost any extra—we added “Son of Isaac W. Chatfield” for a nice touch. (We thought “Beloved Husband of Nellie” would make her roll over in her grave, so we axed that idea). Liz, sitting with arms crossed and furiously gnawing the inside of her cheek, refused to participate, figuring if our grandfather’s wife and children had never erected a headstone for him, they must have had damn good reason—and she wasn’t about to start undoing any family traditions.

grandfather’s (Charles Henry Chatfield) unmarked grave. Gordon and I bought him a headstone. Had I known then about the cobalt blue Bromo-Seltzer bottles, I would have also erected a couple of those for a little color. Instead—and as it didn’t cost any extra—we added “Son of Isaac W. Chatfield” for a nice touch. (We thought “Beloved Husband of Nellie” would make her roll over in her grave, so we axed that idea). Liz, sitting with arms crossed and furiously gnawing the inside of her cheek, refused to participate, figuring if our grandfather’s wife and children had never erected a headstone for him, they must have had damn good reason—and she wasn’t about to start undoing any family traditions.

I’ve gotten to know our family through these stories, interviewing family and dozens of newly found cousins. Like a cub reporter, I’ve detailed those stories here. The diaries, photos, letters, and clippings you’ve saved over the years have made their way into it, with the stories (along with some poetic license) woven in between.

It is most inconvenient having dead relatives. I cannot confirm these stories, hear their versions or ply their memories. I wish I’d cared more when they where here—I would have asked some questions and paid more attention.

Catherine Frances (Clemens) Sevenau, Noreen’s (Babe) youngest child

Charles Henry Chatfield & Nellie Belle Chamberlin Family Line

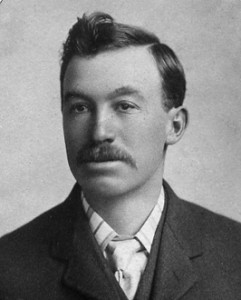

Charles Henry “Charlie” Chatfield

- 6th of 9 children of Isaac Willard Chatfield & Eliza Ann Harrington

- Born: Sep 21, 1870, Florence, Fremont Co., Colorado

- Died: Jul 23, 1942 (age 71), Oroville, Butte Co., California; cardiac failure, senility, malnutrition

- Buried: Jul 25, 1942, Chico Cemetery in Chico, Butte Co., California

- Occupation: Cattle rancher, farmer, butcher, rice farm foreman, Diamond Match, carpenter

- Married: Dec 26, 1894, Nellie Belle Chamberlin, Grand Junction, Mesa Co., Colorado

- Ten children

Nellie Belle Chamberlin

- 1st of 6 children of Finley McLaren “Frank” Chamberlin & Emily S. Hoy

- Born: Mar 7, 1873, Kansas City, Jackson Co., Missouri

- Died: Jan 2, 1956 (age 82), Chico, Butte Co., California; excess choler

- Buried: Jan 4, 1956, Chico Cemetery (Catholic section) in Chico, Butte Co., California

- Occupation: Diamond Match, ran the Eagle Café (Colusa)

- Married: Dec 26, 1894, Charles Henry Chatfield, Grand Junction, Mesa, Co., Colorado

- Ten children: Charles Joseph “Charley” Chatfield, Leo Willard Chatfield, Howard Francis Chatfield, Roy Elmer Chatfield, Nellie Mary “Nellie May” Chatfield, Gordon Gregory Chatfield, Verda Agnes Chatfield, Arden Sherman Chatfield, Jacqueline “Ina” Chatfield, Noreen Ellen “Babe” Chatfield

1. Charles Joseph “Charley” Chatfield

- Born: Nov 18, 1895, Fruita, Mesa Co., Colorado

- Died: Aug 2, 1986 (age 90), Paradise, Butte Co., California; heart attack

- Buried: Aug 6, 1986, Glen Oaks Memorial Park in Chico, Butte Co., California

- Married: Apr 30, 1927, Velma Avis Turnbull, Oroville, Butte Co., California

- Military Service: Mexican Border Campaign; WWI, Army Sergeant 160th Infantry, American Expeditionary Force

- Occupation: Rice rancher, iceman, fruit stand owner, worked for U.S. Steel

- Avocation: 8 mm home movies (mostly of U.S. conservation dams)

- Children: none

2. Leo Willard Chatfield

- Born: Oct 23, 1897, Ten Sleep, Big Horn Co., Wyoming

- Died: Jul 20, 1956 (age 58), Grass Valley, Yuba Co., California; heart attack

- Buried: Jul 24, 1956, Golden Gate Nat’l Cemetery in San Bruno, San Mateo Co., California

- Occupation: Rice rancher, US Forest Service/log-scaler, contractor

- Military Service: U.S. Army, 1914/15: Company I, Red Bluff, Tehama Co., California

1916: WWI, Private, Co I, 1st Republic Regiment, American Expeditionary Force - Married: abt 1933, Ethel Helen (Stirewalt) Zornes

- Two stepchildren: Etta Mae/May Zornes, Joseph Eugene “Gene” Zornes

3. Howard Francis Chatfield

- Born: Jun 13, 1899, Eldora, Boulder Co., Colorado

- Died: Jan 16, 1953 (age 53), Chico, Butte Co., California; Bright’s disease

- Buried: Jan 19, 1953, Chico Cemetery in Chico, Butte Co., California

- Occupation: Levy-Zentner Co., Diamond Match, Union Ice, Mulkey’s store, Chico Meat Co./butcher

- Married: Dec 29, 1919, Evelyn Alice Wilson, Fresno, Fresno Co., California; eloped

- Six daughters: Maye Francis Chatfield, Gloria Jane “Dodie” Chatfield, Patricia Joy “Peaches” Chatfield, Yvonne Jessie “Vonnie” Chatfield, Nadine Evelyn Chatfield, Judith Lynne Chatfield

4. Roy Elmer Chatfield

- Born: Mar 20, 1901, Rifle, Garfield Co., Colorado

- Died: Jul 11, 1978 (age 77), Chico, Butte Co., California; heart failure

- Buried: Jul 14, 1978, Glen Oaks Memorial Park in Chico, Butte Co., California

- Occupation: Diamond Match/mill worker, Chico Ice & Cold Storage/driver, Grey Eagle Lumber

- Married: Aug 1, 1956, Josephine Elizabeth “Jo” Chambers, Reno, Washoe Co., Nevada

- Children: none

5. Nellie Mary “Nellie May” Chatfield

- Born: Mar 11, 1903, Rifle, Garfield Co., Colorado

- Died: Nov 21, 1983 (age 80), Martinez, Contra Costa Co., California; stroke

- Buried: Queen of Heaven Cemetery in Lafayette, Contra Costa Co., California

- Occupation: Diamond Match, Moore Dry Dock Shipyard WWII, Sears & Roebuck, cook/housekeeper for Catholic priests

- Married (1): Apr 17, 1926, Edward Waldon McElhiney, Chico, Butte Co., California

- Married (2): abt 1931, Louis Lee Mote

- Four children: Roy Joseph “Buster/Mac” McElhiney, Mary Ellen Mote (McElhiney) Beverly Joan McElhiney, Barbara Ann McElhiney

6. Gordon Gregory Chatfield

- Born: Dec 20, 1905, Casper, Natrona County, Wyoming

- Died: Nov 19, 1948 (age 42), San Francisco, California; WWII war injuries

- Buried: Nov 23, 1948, Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, San Mateo Co., California

- Military Service: Aug 12, 1942, National Guard, WWII, U.S. Army Air Corps, warrant officer, Private 1st Class

- Occupation: Diamond Match Co., mattress manufacturer, furniture refinisher

- Married: 1929, Hylda Pauline Hughes, prob Colusa, California

- Divorced: bet 1939 and 1940

- Children: none

7. Verda Agnes Chatfield

- Born: Aug 23, 1908, Sanders, Rosebud (now Treasure) Co., Montana

- Died: Sep 26, 1978 (age 70), Chico, Butte Co., California; heart attack

- Buried: Sep 28, 1978, Chico Cemetery (Catholic section) in Chico, Butte Co., California

- Occupation: Ran a boarding house for college girls in Chico, California

- Married: Mar 27, 1927, George William Day, Jr., Chico, Butte Co., California

- Two stepchildren: Robert Elwood Day, George Louis Day

- Four children: Marceline Dolores Day, Leo Ronald “Jim” Day, Judith Lee Day, Jeffery Brian Day

8. Arden Sherman Chatfield

- Born: Aug 29, 1910, Sanders, Rosebud (now Treasure) Co., Montana

- Died: Oct 3, 1981 (age 71) Chico, Butte Co., California; heart failure

- Buried: Oct 7, 1981: Chico Cemetery (Veteran’s Section) in Chico, Butte Co., California

- Military Service: WWII US Army Private, Co. G Infantry Division 184th Reg.

- Occupation: Farm laborer, Chico Ice Co., cook, waiter, busboy

- Avocation: Hobo, traveled the United States hopping trains

- Married: no

9. Jacqueline “Ina” Chatfield

- Born: Feb 24, 1913, Sanders, Rosebud (now Treasure) Co., Montana

- Died: Feb 17, 1993 (age 80), Yuba City, Sutter Co., California; old age/heart

- Buried: Catholic Holy Cross Cemetery in Colusa, Colusa Co., California

- Married: May 22, 1932, James Leroy Fouch, Reno, Washoe Co., Nevada

- Three children: Joanne Arlene Fouch, Shirley Jean Fouch, James Edward Fouch

10. Noreen Ellen “Babe” Chatfield

- Born: Sep 29, 1915, Los Molinos, Tehama Co., California

- Died: Nov 9, 1968 (age 53), Whittier, Los Angeles Co., California; suicide

- Buried: Cremated/niche Memory Garden Memorial Park in Brea, Orange Co., California

- Occupation: Family variety store, seamstress, cook/housekeeper for priests

- Married (1): Feb 4, 1933, Carl John Clemens, Colusa, Colusa Co., California

- Divorced: Dec 1953, Sonora, Tuolumne Co., California

- Five children: Gordon Lawrence “Larry” Clemens, Carleen Barbara Clemens, Elizabeth Ann “Betty/Liz” Clemens, Claudia Clemens, Catherine Frances “Cathy” Clemens

- Married (2): Jul 31, 1955, Raymond D. Haynie, Carson City, Ormsby Co., Nevada

Lore, Libel and Lies

My father was German and my mother was English, which could explain everything. On my father’s side I’m a generation removed from hardworking, God-fearing, church-going, tight-laced, thin-lipped, duty-bound dairy farmers—on my mother’s, I come from a clan of free-wheeling, drinking, smoking, gambling, hell-raising cattle ranchers with a couple of righteous Catholics thrown in for a dash of temperance. My maternal relatives had more fun. I can tell from their stories. Most of them didn’t see much worth in being good—except of course my Grandma Nellie Chatfield, who was of the opinion that rectitude was required behavior (and the higher she stood on her moral ground, the lower her family descended). I tend to take after Grandma Nellie and my father’s side of the family. How unfortunate for me, and for those around me—especially those who tend not to behave.

Nellie was the daughter of Finley McLaren “Frank” Chamberlin and Emily S. Hoy. Emily’s parents died when she was a young girl and she was left in the care of her mother’s cousin. On Jan 1, 1864, (this was during the Civil War), 13 year-old Emily was enrolled in the Wheeling Female Academy, a Catholic boarding school in Wheeling, West Virginia. Devoting herself to God, she became the first Catholic in the family. In her senior year, she asked her older brothers’ permission to become a nun; they immediately unenrolled her. Removing to Kansas she was soon married to a philanderer and not long after, (shortly after leaving him), had her first child. She then married Finley Chamberlin, a train conductor and recent Civil War veteran, and six more children followed, my grandmother Nellie being the eldest of that brood. Emily passed her strong Catholic beliefs to Nellie; she also passed on her insistence of strict obedience, family duty, moral rectitude, and the ability to make it on her own.

Dec 26, 1894: Marriage of Charles Henry Chatfield and Nellie Belle Chamberlin, in Grand Junction, Mesa County, Colorado.

In Dec of 1894, when he was twenty-three and she was twenty-one, Charles Henry Chatfield, my grandfather, married Nellie Belle Chamberlin. Nellie was exceedingly religious, but was strong-willed and had a mind of her own. She refused to consummate their marriage. In frustration, Charles took his new wife to the Catholic priest who had married them and explained the situation. Father Carr sat Nellie down and told her to go home and be a good wife to her husband. She got the message, bearing her first child nine months later—and, being the good Catholic she was—delivered nine more over the span of the next twenty years.

Nov 18, 1895: Birth of Charles Joseph “Charley” Chatfield, 1st child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, at the home of Nellie’s parents in Fruita, Mesa County, Colorado.

Oct 23, 1897: Birth of Leo Willard Chatfield, 2nd child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Ten Sleep, Big Horn County, Wyoming. Nellie is in Ten Sleep for the birth of her 2nd child (Charles parents, I.W. & Eliza Chatfield are living there). Charles’ brother, Elmer Chatfield, also has a large ranch in Ten Sleep.

Jun 13, 1899: Birth of Howard Francis Chatfield, 3rd child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Eldora, Boulder County, Colorado. (Eldora is now a ghost town, part of the Roosevelt National Forest, Boulder County, Colorado.)

1900: Charles, Nellie and their three small boys move to Rifle, Colorado.

Mar 20, 1901: Birth of Roy Elmer Chatfield, 4th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Rifle, Garfield County, Colorado.

Mar 11, 1903: Birth of Nellie Mary “Nellie May” Chatfield, 5th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Rifle, Garfield County, Colorado.

Dec 20, 1905: Birth of Gordon Gregory Chatfield, 6th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Casper, Natrona County, Wyoming.

Aug 23, 1908: Birth of Verda Agnes Chatfield, 7th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Sanders, Rosebud County, Montana.

Aug 29, 1910: Birth of Arden Sherman Chatfield, 8th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Sanders, Rosebud County, Montana.

June 12, 1911: Death of Eliza Ann (Harrington) Chatfield (age 71), mother of Charles Henry Chatfield, in a hospital in Basin, Big Horn County, Wyoming, of uterine cancer.

Feb 24, 1913: Birth of Jacqueline “Ina” Chatfield, 9th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Sanders, Rosebud County, Montana.

In 1913 news came from kin in California about the golden opportunities there: land was cheap, the weather was mild, and rice was the big new crop. Grandpa Chatfield was a highly successful rancher but Nellie was tired of the cold in Montana and persuaded her husband to sell their holdings and join the relatives out west. Completing most of the preparations for the move, Charles rode into town to finalize the sale. Four days passed, so Nellie sent a hired hand to look for him. He found Grandpa drunk—and found that he’d also gambled away all their money.

Nellie remained determined to move and went to sell the only property they had left—a wagon and a team of horses. There was a ruckus over the ownership of the wagon with the new caretakers, the Popp’s, who were taking over managing the Meyerhoff place. When the Popp’s attempted to stop her, Nellie’s two oldest sons stepped in. Subsequently Charley and Leo were brought before the judge and fined. Nellie went ahead anyway and sold the wagon and horses for $300, purchasing train tickets.

This wasn’t the first time Charles gambled away their family holdings, nor would it be his last; he had a reputation as a drinker and a gambler, at times bringing home very little to support the family. His vices infuriated Nellie, her heart crimping, her back turning—cold and sour—so resentful you tasted her bile. The loss of the ranch was the rustiest nail, leaving her embittered for life.

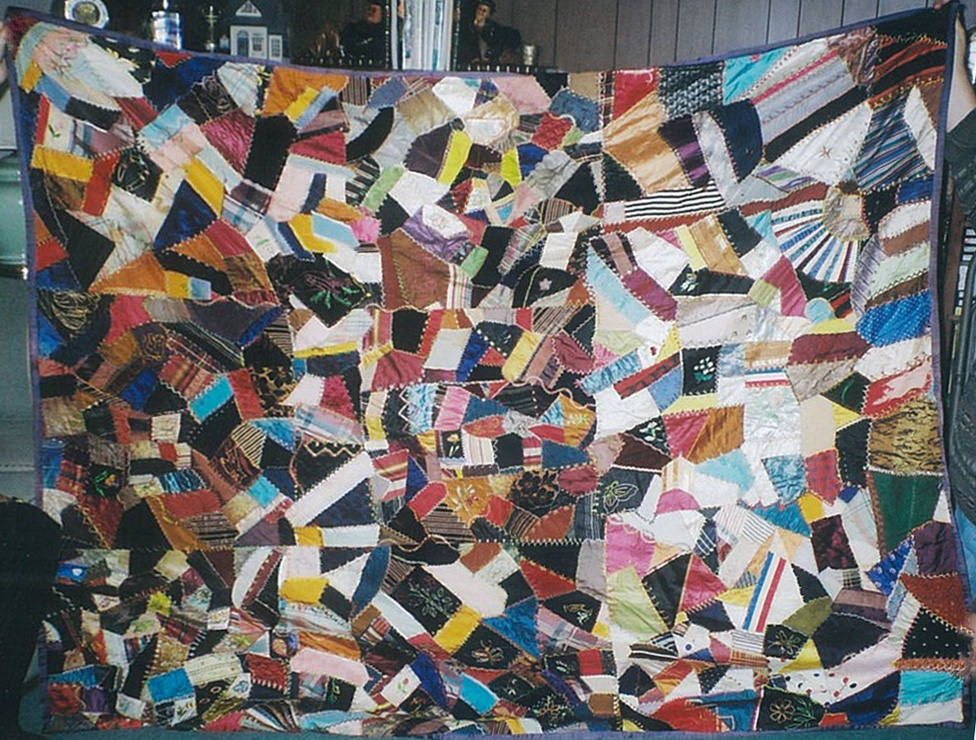

As Nellie readied her household for the long train-ride to California, she said nothing as she crated her New Haven kitchen-clock, a gift from her husband at the birth of their first child. She said nothing as she boxed her glass-jarred button collection, her sewing needles, and her nearly completed crazy quilt—a crayon-colored piece she’d started during her first pregnancy. She said nothing as she packed her trunks with her high-necked blouses, her bloomers and petticoats, nothing as she packed her linens, her pictures and books, nothing as she packed her black cast-iron pots and her pans and her past. With Nellie, wrath was silent.

With tickets in hand and nine children in tow, she boarded the train at Sanders, leaving Charles behind. Nellie was forty when she left Montana with a cracked marriage and broken foot. (In a fit of venom while ironing her traveling skirt, she had dropped the heated sad iron on it, boarding the train in a wheelchair.) Charley, seventeen and the oldest child, carried his silver timepiece and a small leather-bound pocket diary. Leo, two years younger, carried his case knife. Howard, a scrappy fourteen-year-old, carried a chip on his shoulder. Roy, not quite eleven, stayed close to Nellie; he carried the food baskets and what was needed for the little ones. Her first girl, Nella May, a wisp of a child not yet ten—had her hands full hanging on to Verda who was four and tow-headed Arden who was two-and-a-half. Gordon, seven, carried his mother’s hatbox. Tiny three-month-old Ina was in the crook of her mother’s arms.

Note: The body of a sad iron was cast hollow and filled with material that was a non-conductor of heat—such as plaster of Paris, cement or clay—which held the heat longer so that more garments could be ironed without reheating the iron. The word sad meant heavy or dense.

1913: Los Molinos, California Upon arriving in Los Molinos, California, Nellie’s father-in-law, Isaac Willard Chatfield, met them by carriage at the Southern Pacific depot. There were too many to put up, so he escorted Nellie and his nine grandchildren across the road, ensconcing them in the Los Molinos Inn, a temporary way station for people coming to California.

The Inn was built in 1905. It was an elegant, three-story, half-timber structure occupying three blocks in the center of town, surrounded on three sides by a wide porch that shaded the guests from the overwhelming heat of the Los Molinos summers. Behind the hotel was a row of white painted housing for the workers. A Japanese gardener serviced the lush grounds, his huge and carefully tended garden supplying fresh fruits and vegetables for the cooks in the kitchen.

(In December of 1956, the Los Molinos Inn burned to the ground when the roof caught fire from burning Christmas wrappings. The hotel safe and the forged metal fireplace andirons were the only pieces to survive the inferno.)

Charles arrived in Los Molinos three days behind his wife and children, hat in hand. Nellie may have taken her wayward husband back, but she refused to forgive him. She also refused to share her bed—although she must have once—as their tenth child, my mother, was born two years later. They named her Noreen Ellen, but everyone called her Babe.

1913 to 1915: The Chatfield’s live in Los Molinos, Tehama County, California where the children attend school. Nellie and her children travel over the bridge every Sunday to the adjoining town of Tehama to attend the Catholic Church. Also living in California are:

Emily (Hoy) Chamberlin (Nellie’s mother), Hollywood, Los Angeles County

Isaac W. Chatfield (Charles’ father), Princeton, Colusa Co. and then Oakland, Alameda County

Jacquelin Mallon (cousin) & husband Jim Mallon are rice ranching in Princeton, Colusa County

Mabel Chatfield (cousin), is married to George Sawyer and living in Hemet, Riverside County

Mary (Morrow) Chatfield (aunt) and her daughter Marjorie (cousin), Chico, Butte County

1914-1918: First World War (also called The Great War and the War to End All Wars).

During the First World War, Nellie supplemented the family income by raising caged guinea pigs in her overgrown yard and selling them to the U.S. army who used the shy creatures for running in the trenches to detect mustard gas.

After the war she and her children gathered the fallen black walnuts from her numerous trees, spending the walnut season husking and shelling the tough nuts, their fingers cracked and stained from the black outer shells, packing the freshly cleaned nuts in pint and quart glass canning jars and selling them along side the road, making a goodly sum.

Sep 29, 1915: Birth of Noreen Ellen “Babe” Chatfield, 10th and last child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Los Molinos, Tehama County, California.

California was not the land of flowers as Nellie had hoped—but the weather was better. The family settled

in Los Molinos where life was spare and my grandmother made do. Charles rice-farmed and Nellie raised the children. He puttered and tinkered in his garden. She scrubbed floors and cooked stews and mended shirts. He fed his chickens. She kneaded her bread, adjusting her baking habits to the climate and the train schedule. Every afternoon she waited for the whistle and clanking train cars to pass. Lifting her long skirt to hike the slight incline up to the tracks, she bent down and carefully balanced her cloth-covered tins of dough on the hot iron rails; it was the only way she could get her breads and cinnamon buns to rise.

1915: Los Molinos Starting her family and her hand-stitched crazy quilt in Colorado, Nellie completed them both with the birth of my mother. In 1895, during her first confinement (pregnant and nursing women were not seen in public, even to attend church), the quilt began to take shape.

Her fine hands stitched rivers of gold, roads of onyx, and fences of pearl, connecting salvaged pieces of fabric—of little girls petticoats, of Sunday-go-to-meetin’ bests, of Grandpa’s fine vest, a bit of a wedding dress, a narrow strip of a cambric shawl. Patches of stripes and checks were stitched and cross-stitched with a jigsaw of shapes and hues: brocade rectangles of ochre and mustard; satin triangles of emerald and indigo; poplin squares of carmine and pale rose; fine wools circlets of cerulean and violet. She saved her sewing scraps in a flour sack until she had a quiet moment to stitch the patchwork of smooth velvets, shiny taffetas and bumpy poplins into a multicolored canvas for her embroidered birds and butterflies and sweet honeybees that winged across her quilted legacy.

Over the years her bridle paths of alabaster threads gradually defined a landscape: a random patchwork of cattle-ranches, rice fields and farm lands as if viewed through the keen eyes of a soaring red-tailed hawk. In her ankle-length skirts and her high-necked long-sleeved blouses, Nellie rocked in her chair, her children in bed, her round sewing frame on her lap—silently laboring over her quilt, her only time of peace and solitude. By the gas lamp she stitched zigzags of rainbow, dapples of color and splashes of hope, creating a cover considerable enough to warm a generation of Chatfield’s.

As the family traveled by horse and buckboard through dust and storm, homesteading parts of Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana, the blanket, carefully folded and boxed, traveled with her. I can’t imagine living through those times—through the harsh Rocky Mountain summers and winters, praying for better weather, for water and a good crop, for relief from the grasshoppers and the mosquitoes and the incessant biting of horse flies. Praying for her children down with whooping cough, croup and ague—supplicating, kneeling, genuflecting—praying to God for everyone—but herself.

I can’t imagine every day having to haul water trying to keep things clean. Making one-pot meals in a black cast-iron kettle. The daily baking of buttermilk biscuits and apple cobblers and rough wheat breads. Canning bushels of peaches and rows of corn to make it through another winter. Snow to shovel. Wood to chop. Constant mouths to feed. Rain. Mud. Snow. Animals dying, blizzards, buckboards, wagon trains, rattlesnakes, tornadoes, droughts—and babies. Twenty years of birthing, nursing, rocking, bathing, and changing crying babies. Although Nellie wouldn’t have taken a million bucks for any one of her children—she wouldn’t have paid a nickel for another.

Maybe my grandmother’s crazy quilt kept her sane. With the passage of time, like the passage of her family, its threads—winding and wandering through the generations—have worn, frayed, and unraveled. But like her family, its colors have withstood, endured and upheld the tapestry of life. Brilliantly.

Note: The quilt is in the care of Ina’s daughter, Nellie’s granddaughter. The backing was refurbished as it was fraying, and it is now in wonderful condition.

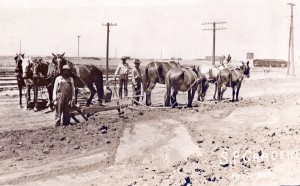

In the first year of moving to Los Molinos, Grandpa acquired a team of twelve draft horses and during the yearly April and May planting season hired himself out to local farmers in and around the rice towns of Princeton, Williams, Maxwell, and Colusa. The area was the largest rice-producing region in the state, the Sacramento River keeping the soil inundated with water, the heavy clay unsuitable for most crops was perfect for rice. My grandfather acted as the work crew foreman, traveling from farm to farm (including farms and ranches owned by the Chatfield’s and Mallon’s). Charles’ three oldest sons (who had quit their schooling as young boys to work on the family cattle ranches in Wyoming and Montana) now worked alongside their father in the fertile green fields of California. Education was not a priority for ranchers and farmers in those days—survival was.

Charley and Leo (until they went away to fight in the Great War) and Howard (until he eloped with his English sweetheart) worked the horses. In a race to beat the September and October rains, Charles’ crew retraced their route throughout the area harvesting the rice crops they sowed six months before.

Grandpa brought home very little of what he made in the rice fields, gambling most of it away. Attempting to buy his way back into Nellie’s good graces, he extended a peace offering, a small gift wrapped in cloth. She thought it was his earnings for the week. It wasn’t—it was an elegant tortoise shell comb for her long dark hair that she only let down at night. “You fool!” she snapped. “We need food, not frivolity,” and hurled his offering at his chest. “What you wasted on this could have gone to feed us for a week!”

Nov 1915: Chico, California In 1916 the Chatfield family left Los Molinos and moved to the up and coming agricultural town of Chico, buying a fairly new two-story corner residence on Boucher Street in the Chapmantown district, a working-class neighborhood near the Diamond Match Factory. In those days most people rented; few owned their own homes. With only two upstairs bedrooms, the boys sharing one, the girls the other, it was small house for a large family. Downstairs, Grandma Chatfield created a tiny sleeping space for herself in an alcove under the stairway, keeping the small downstairs bedroom for company. Grandpa slept in the shed.

During the First World War, Nellie supplemented what little income the family had by raising caged guinea pigs in her overgrown yard and selling them to the U.S. army who used the shy creatures for running in the trenches to detect mustard gas, like caged canaries are used for detecting gas in coal mines.

After the war she and her children gathered the fallen black walnuts from her numerous trees, spending the walnut season husking and shelling the tough nuts, their fingers cracked and stained from the black outer shells, packing the freshly cleaned nuts in pint and quart glass canning jars and selling them along side the road, making a goodly sum.

The family had a dog named Poofer for a few years—the only pet they ever had.

In 1919, tractors replaced the horse teams. Charley and Leo came home from the Great War and Howard returned to Chico with his young English wife and under Nellie’s threat to have their marriage annulled—remarried her in the Catholic church. By the end of 1920, my grandfather—along with his team of twelve horses—was put out to pasture.

Nellie, in the early 1920’s, worked at the Diamond Match Company, employed as a wrapper, a floor lady, and then as a supervisor. In 1926 and 1927 Charles worked there, and at various times in between, so did their children: Gordon and his wife Hylda, Verda, Roy and his sweetheart Jo.

Diamond Match was one of the largest manufacturing companies in America. The railroad line skirting the Chico plant carried lumber directly from its Stirling plant mountain operations and stored the dry lumber in the Chico yard until processed. The largest employer in Chico until its doors closed in 1958, it manufactured wood matches and matchboxes, doors and sashes, veneer and plywood, wooden produce boxes, apiaries and bee-keeping supplies. Much of the timber went to build the stately homes in San Francisco. It was a huge enterprise that included a machine shop, foundry, and mill works along with an employee social hall, baseball diamond, and badminton courts. The west end of 16th Street led directly into the 133-acre site and was within walking distance of 1543 Boucher Street.

Apr 17, 1926: Marriage of Nellie Mary “Nellie May” Chatfield and Edward Waldon McElhiney (5th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin), in Chico, Butte County, California.

Mar 26, 1927: Marriage of Verda Agnes Chatfield and George William Day, Jr., (7th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, In Chico, Butte County, California. George is a widower (ten years Verda’s senior) with two children.

Apr 30, 1927: Marriage of Charles Joseph Chatfield and Velma Avis Turnbull (1st child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin), in Oroville, Butte County, California.

1929: Marriage of Gordon Gregory Chatfield and Hylda Pauline Hughes (6th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin), in probably Colusa, Colusa County, California.

Abt 1931: Marriage of Nellie Mary “Nellie May” Chatfield and Louis Lee Mote (5th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin), her second marriage.

May 22, 1932: Marriage of Jacqueline “Ina” Chatfield and James Leroy Fouch (9th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin), in Reno, Washoe County, Nevada.

Abt 1933: Marriage of Leo Willard Chatfield and Ethel Helen (Stirewalt) Zornes (2nd child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin).

Feb 4, 1933: Marriage of Noreen Ellen Chatfield and Carl John Clemens (10th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin), in Colusa, Colusa County, California.

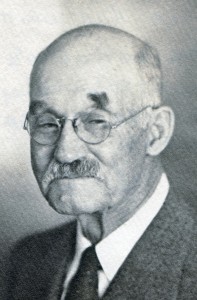

It seems Charles Henry Chatfield, my grandfather, was seldom around and hardly anyone remembers him. Like many of the Chatfields, he was a small man, maybe 5’4”, and trodden smaller as time went by. When he wasn’t away working he spent most of his time in his garden with his Leghorns, his sleeping quarters the large back yard shed, his cot sharing his space with kindling brought home from the Diamond Match Factory. He didn’t have to account for his gambling and drinking if he wasn’t around Nellie. The older boys bunked with their father as they too no longer wanted to account to their mother their comings and goings. He had a mustache his whole life, only shaving it off once. The minute his children saw him without it they laughed themselves silly; he slunk into his garden among his chickens and chard.

His drinking didn’t help his burning dyspepsia so he kept a supply of Bromo-Seltzer on hand. Each time he finished a bottle he planted it upside-down in the dirt in his part of the yard, separating the length of the lawn from the sidewalk, his cracked and calloused hands carefully constructing a decorative three-inch high hedge of cobalt blue, adding a little color to his life.

Summer 1939: Chico The then thirteen-year-old granddaughter of his older brother Elmer recalls meeting Grandpa in the summer of 1939 when she (Beverly Sproul) and her family stopped in Chico on a month long road trip from Wyoming. For some reason, Grandma turned away at her brother-in-law’s greeting—but Nellie seldom hid her opinion of the sins she held against others. If she didn’t like someone—or anyone related to that someone—if there was some offense, some fault, some fatal flaw, you simply weren’t welcome in her home.

Grandpa and Elmer hadn’t seen each other in years and they had a lot of catching up to do. The brothers wandered into the back yard. Grandpa showed off his chickens and his garden, bending to pull a weed as they chattered on. They talked of their children, of Ella and Callie, their sisters whom Grandpa hadn’t seen in forty years either. Elmer had just come through Globe and Superior, Arizona, where their two widowed sisters lived. Ella was so taken—she hadn’t seen her brother for forty years. Elmer was not a big man to begin with, and Ella was smaller still. She leaned her head against her younger brother’s chest and sighed “oh El.” Her lids hung over her eyes and she had them taped up so she could see. They stayed in Arizona a couple of days. Beverly remembers Ella walking by her collection of lead crystal on the buffet, Ella flicking them with her finger to listen to it ping. That’s how you tell it is crystal.

They conversed about Elmer’s ranch in Wyoming, the price of sheep and cattle, what rice farming was like in California. In the meantime, Elmer’s daughter Sevilla and her thirteen-year-old girl Beverly sat on the porch with Nellie. Sitting stiffly in her slide rocker facing her husband’s kin, arms cemented across her chest, feet lodged on the floor, her glare piercing through them, Nellie’s starched skin scratched the air—not a word escaping from her mouth. She had nothing against them in particular. They just happened to be related to Elmer and were paying for whatever offense he may have committed, which simply may have been that he was related to her husband. They didn’t stay long, and it was their one and only visit.

They went onto Jim and Jacqueline Mallon’s place for a big family reunion at their ranch in Orland. Jacqueline was almost six foot, which was extraordinarily tall for a Chatfield. The reunion was only an hour from Chico. Thirty of the Chatfield cousins from the area were there. Most of them were there, all except Nellie and Charlie.

Elmer and his family looped over to Southern California to see Elliott and Sophie Shaw, then stayed with family in Los Angeles who took them out to the horse ranch to see Sea Biscuit—who’d been put to pasture by this time—but was still beautiful. Then they drove their four-door robin blue 1939 Lincoln Zephyr to Santa Monica to see his youngest sister Calla who was also a widow, and her children Jane and Bob. She lived with her gorgeous grey Persian cat that stayed up on the mantle.

From there the three headed up looking for Marion, Elmer’s daughter who had disappeared from the family some years before. They drove through town after town, through Grass Valley and Placerville and never were able to find her. They decided she didn’t want to be found. Her husband had walked out on her and she and her three small vanished and were out of touch with the family.

Elmer returned to Wyoming and never saw any of his brothers and sisters again.

The Chatfield children feared their mother’s wrath. Freely extending her feelings, opinions, and judgments, Nellie didn’t keep secret the sins she held against them, and they feared what she would say. If Grandma didn’t like someone, or anyone related to that someone, if there was some flaw, some fault, some fatal lack, you were not welcome in her home. She seldom changed her mind about any opinion she held of you.

Grandma Chatfield was a fine cook, preparing one-pot meals on her wood stove as her mother did, and her mother’s mother before her. Nellie passed on these dishes to her daughters. Simmering beef stew, chicken rice soup, kettles of hamburger chili, pots of spaghetti and meatballs. In her heavy skillet—with the bacon grease she saved in coffee cans—she scrambled cow’s brains and eggs, fixed kidneys with gravy and mushrooms, sautéed sweetbreads with buttons and pearls, fried liver with onions, and boiled tongue for tongue sandwiches. She also taught her girls to bake: biscuits, cornbread, oatmeal and sugar cookies, angel food and chocolate cakes, apple and cherry pies, sweet cinnamon buns—and to can, the shelves on both sides of the cellar stacked from floor to ceiling with glass canning jars filled with seasonal fruits, jams, jellies, tomatoes, corn, green beans, peas, and mushrooms, all sealed with paraffin and glass lids and metal sealing clasps.

Sitting down one day to a meal with all ten children at the table, Grandma proudly noted that the Chatfield name would never die out, her having six fine sons. As it turned out, five of the boys never had children, and Howard, the only son who did, had all girls. There were a lot of Chatfield children living in Chico. With six of Grandma’s children and then Howard’s five daughters (his oldest was five years younger than Babe) in the school system at the same time, the local teacher looked over her spectacles while reading the roster at the beginning of a new school year and inquired, “Is there no end to you Chatfield’s?”

As Nellie aged, she seldom left her platform rocker other than for daily mass, her ear glued to the Philco, listening like millions of others to H.V. Kaltenborn, a popular 1930’s and 40’s CBS radio news commentator. Her feet bothered her a lot over the years; she had “burning feet”, probably caused from wearing shoes too small; later in life it hurt her to walk. Maybe that’s why she seldom smiled.

During the wet winters, her upholstered slide-rocker was moved to the south wall of the family parlor facing east where she warmed by the pot-bellied stove in the middle of the room, rocking back and forth and fingering her rosary beads. In the sweltering summer her chair was moved to the front window in the family parlor where she rocked all day long on the raised dais, allowing her to have a better view out her front window, her black table-fan and her hand-fan slowly moving the oppressive summer heat around her in circles. From her comfortable chair she kept a sharp eye on everything going on inside her home and outside her window at 1543 Boucher Street.

1940’s: Chico Despite her unwillingness to accept non-Catholics within her family, despite her inability to accept divorce, and despite her rabid disapproval of drinking, gambling, smoking, cussing, and fighting, Nellie’s children respected her and loved her, and still got together often. In the 1930’s and 40’s, many of the Chatfield clan visited at the Boucher Street house, their children playing in the front yard or off swimming or fishing during the day, sleeping on the screened porch at night. Grandma’s sisters, Ada and Mamie, visited every year. Roy was their chauffeur, driving Aunt Ada, Aunt Mamie and his mother in his black Terraplane around Chico and over to Sacramento to go shopping. Grandma was always glad to see her sisters.

My sister Claudia was afraid of them. The first time she saw them at Grandma’s house they were dressed in long dark clothes and black hats; when the two aged women bent down to kiss her, my small ringlet-rimmed sister suspected they were witches—and flew from the room screaming.

Grandma was old, born in 1873, and even though her sisters were younger, in their fifties and sixties, they seemed old too: Ada was born in 1877, Mamie, ten years later. Grandma was always glad to see her sisters and her brothers, Fred, Roy and Willard. The Chatfield’s were small, under 5’ to 5’5”, and they grew smaller as they grew older. They also have a tendency to droopy eyelids. As they age, they have to tip their heads back to see past their lids, their shielded eyes looking like two’s-of-diamonds, and their throats get a narrowing so they constantly clear them, choking at times when they swallow.

Grandpa moved to Bolinas for a few years and built himself a house there. His last five years he lived alone in a cabin near Forest Ranch, a small mining town between Chico and Butte Meadows, a town with little more than a post office, a bar, and my grandfather, and in Lomo Crossing, which was little more than a levee, a train station, and my grandfather. During the years he lived in Chico, he raised chickens, took care of the trees, and tended the garden; when he lived in Forest Ranch and Lomo Crossing, he did the same.

Grandpa Chatfield passed away in 1942; during the funeral procession the only thing Grandma had to say was, “Serves the drunken old fool right.” (The women in my family have a tendency to hold on to things.) Still unwilling to pardon him for gambling away the family fortune some thirty years before (though I can’t say I blame her), she buried him in the non-Catholic section of the cemetery, away from the family plots, no headstone, no small cross, not even an upside-down blue bottle to mark his grave. He left no estate and it’s possible she simply couldn’t afford a headstone (she only had her old age pension), but his children didn’t buy him one either. His unmarked grave lies quietly at the corner of a large storage shed, a familiar place for him.

Jul 23, 1942: Death of Charles Henry Chatfield (age 71) at the Butte County Hospital in Oroville, Butte County, California, of cardiac failure. He had heart disease, and contributory causes to his death were senility and malnutrition. He was living up near his son Leo at the time he took ill.

By 1943 my parents had four children (I didn’t come along until 1948) and settled in Sonora. Every summer they spent a week or two at the Chatfield home on Boucher Street in Chico. By then Grandma Chatfield, a seventy-year-old woman tired of people, said little more than hello unless she took a cotton to you. She did enjoy pleasure from some of her grandchildren; her first grandson, “Buster”, was the apple of her eye. Ina’s girls, Shirley and Joanne, have fond memories; Verda’s children’s memories are not so fond. Larry was her only grandchild in our family she hugged and kissed. Once, and only once, she kissed him on the lips! So surprised, he almost fell over it made him so nervous. Then again, anyone hugging or kissing my brother makes him nervous.

Chico was even hotter than Sonora during the summer, in the 100’s every day. The family took daily picnics to Bidwell Park and swam in the icy Sycamore Pool dammed off from Big Chico Creek. The fresh water creek flowed continuously through it, cement encasing the 700-foot long pool built in 1929, lined on both sides with grassy slopes shaded by towering white-barked sycamores and majestic valley oaks planted by General John Bidwell. The park was the jewel of Chico. Mom liked to fish and took the kids, baiting their hooks with worms for perch and blue gill. She used pink salmon eggs for trout, which Betty always tasted, wondering what people saw in the delicacy. My sister ate anything. As a youngster, Mom, with her brothers and sisters, fished at Big Chico Creek, spending the long days on the rocks under the big shade trees, their lines dangling in the water. They used safety pins for hooks, no bait, just the opened pins. It didn’t matter that they didn’t catch anything—they just liked fishing.

Larry and my three sisters loved going to Chico because of Grandma’s books. There were piles of them all over the house. She had western literary genre about Wyoming, Montana and Colorado, places where she and her family lived, books by Booth Tarkington, the two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, books by Owen Wister and McLeod Rainey. The Magnificent Andersons, The Virginian, West of the Pecos, and Riders of the Purple Sage were in her collection, she and her sisters signing the inside page and exchanging them as gifts. Betty read everything she had. Claudia loved Grandma’s twenty years of yellow-covered National Geographic. Larry and Carleen spent hours in the parlour, poring over Grandma Chatfield’s dusty volumes of World Encyclopedia, reading them from cover to cover; we didn’t have a set at home. (The ninth planet in our solar system, Pluto, wasn’t even in it yet.) She had purchased it from a door-to-door salesman.

Grandma Chatfield was a sucker for the door-to-door salesmen peddling their wares, pitching anything and everything, from potions to lotions, from World Books to prayer books, from Fuller brushes to kitchen knives. She looked forward to their knock on the door, these hawkers who could hawk just about anything–and did—especially to my grandmother.

Daddy was her favorite son-in-law, and she liked Ina’s husband, Jim, so ours were the only families who ever stayed long. Some of Grandma Chatfield’s children, along with their children, didn’t stay long enough to even go to the bathroom, partly because Grandma was so inhospitable, but mainly because they had to use the out-house as there was no indoor plumbing. The Clemens’ and Fouch’s didn’t mind—they were used to camping. When we stayed over, Mom kept a white porcelain pot under the bed for the kids to use at night so they wouldn’t have to find their way out back in the dark. The Fouch’s visited often, and the kids never had a complaint about going. They stopped at Hoyt’s Donut Shop to go to the bathroom before going to the house, and they got a donut, a big treat, to take with them.

When Grandma Chatfield fell and had to go to the hospital in 1947, her sons surprised her and installed a toilet on the back porch. She said she would never allow one in the house; she thought them unsanitary, and as she had been living with an outhouse for so long, she didn’t think anything of it. She also didn’t want her children doing for her, didn’t want to take from them. Ina sent her checks for her birthdays knowing she could use the money, but Grandma sent them back with a note, “You keep it. You need it.” It was not until 1953, three years before she died, that the dark house with tiny rooms was remodeled and a bathroom built inside.

Up until then the family bathed in the kitchen. The large round aluminum washtub hanging on the porch was brought in and filled with water from the kitchen pump handle and heated on the wood stove. The older girls shared the bathwater and the small children, as many as could fit in the tub, all bathed together. When their baths were done, the gray water was bailed outside. Grandma washed her hair with the rainwater she collected in pots on the porch and she scolded her grandkids when they floated their paper boats in it. (Collecting rainwater was common practice in those days, and you didn’t touch it. There was a wooden lid placed over the rain barrel after a storm.) It was soft water, not hard like well water, and she didn’t want the children spilling it. When she was younger her hair was a soft brown and went past her waist; she wore it in a tight bun, only letting it down at night to brush it.

Grandma Nellie’s bedroom was a tiny alcove with a curtain hung for privacy, shielding her twin bed and small dresser at its foot. Everyone was forbidden to go near her space. Under her bed she kept hidden a large flat coat-box with her burial clothes folded neatly inside: a gray shroud, a slip, a pair of white cotton underpants, a girdle, a new pair of shoes, and silk stockings. Grandma always thought she’d die young. Her children were aware of its existence and respected their mother’s privacy. When Mom (Noreen) and her kids came to Chico, Mom threatened that if they didn’t behave she would make them look at Grandma’s shroud to keep them in line. On one of Mom’s visits, Nellie had gone into her funeral box and upon finding the stockings rotted, she sent Mom to the store to replace them. (Roy, who was 55 and still living with his mother, had to replace them again when Grandma passed away.)

Jun 1948: Letter from Ina (Chatfield) Fouch to her mother Nellie:

Dear Mom,

I thought I would drop you a line or two, even tho there isn’t much to write about. Was wondering how you’re surviving the hot weather. Weren’t some of those days terrific though?

Did Arden ever show up Chico again? He got off at Gridley and was wondering if he got a job there, or moved on? One never can tell about him.

I hope to have some tomatoes, etc., for you when Verda comes thru altho the tomatoes aren’t doing very good. We are hoping these later ones will be better. Hope to be able to get you some peaches too.

I gave Jim a little birthday party last week. He was quite thrilled as it was his first birthday party. Shirley sent him the nicest suede cowboy jacket, but it is a little hot to wear it right now. He wears it for about 5 minutes at a time.

Well, I have an ironing to do & want to get at it before it gets too hot so will sign off.

Hope you are feeling better and the heat isn’t bothering you much.

Love to you both,

Ina

Nov 19, 1948: Death of Gordon Gregory Chatfield (age 42), 6th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in San Francisco, California; of complications from his injuries suffered during the time of WWII.

1952: Chico In the last years of her life she had a television set, watching rubber faced Milton Berle from her slide-rocker. In 1952, her favorite show was Bishop Sheen’s Holy Hour. Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, a writer, a preacher, a teacher, was an evangelist of the airwaves. His holy hour, not an hour of devotion, was a sharing of his work of redemption. He pleaded for an hour of companionship, bringing converts to the Catholic Church. He wrote in the chapter on Mystery in his book On The Nature of Our Minds, “Every human being at his birth has everything to learn. His mind is a kind of blank slate on which truths can be written. How much he will learn will depend on two things: how clean he keeps his slate and the wisdom of the teachers who write on it.” Nellie Chamberlin Chatfield, who perceived herself as appointed warden and keeper, thought he said it was her job to keep her eye on everyone else’s slate.

If it is a habit of the righteous to believe one’s soul may be saved by going to church, if attendance on Sundays could make one virtuous, and if attendance on holy days could ensure one’s holiness, then going every day would certainly earn one a seat at the right hand of God —the best seat in the house for one dispensing virtuous judgment. Every morning, for thirty-seven years, Nellie attended St. John the Baptist Catholic Church every morning for thirty-seven years. Even if she took seven years off for bad behavior, vacations, illness or emergencies, that would still leave thirty years: which comes to 360 months, or 1,140 some weeks, or 10,950 days for her to sustain and strengthen her moral superiority. With her rosary twisted, she was here to judge the world, not save it.

Watching the Ed Sullivan Show, she thought the Rockettes scandalous, horrified by their skimpy skirts and bare legs kicked up over their heads, showing more than she had ever seen. She insisted they were sinful. She also insisted the small black and white television not be turned off so she could watch, leaning forward and cleaning the dust specks from her wire-rimmed glasses.

Jan 16, 1953: Death of Howard Francis Chatfield (age 53), 3rd child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Chico, Butte County, California; of Bright’s disease.

Letter From Grandma Chatfield to Nella May:

Dear Nella May,

For goodness sake don’t worry about me. Roy gets worried & excited so easy & there is no need notifying any others. I don’t know what really was the matter with me this last time. I was not in much pain, only just couldn’t seem to get my breath. I don’t suppose you ever heard a wind broken horse, well that is exactly the way I sounded. You could hear me all over the house.

The Dr. heard me before he reached the house. He gave me a BIG shot in each arm. Roy held my arms & said I never flinched, but it sent me out of my head. Those hypos never did that before, but if I said the things Roy said I did, I was out of my head. Those shots must have did the work because I was breathing alright by the time I reached the hospital. I was in no pain, but was still coughing & when I did cough you should have seen those nurses move off.

They took all kinds of X Ray pictures & blood tests & for 36 hours they fed me thru the veins. Then when they wanted to put tubes in my nose & down my throat, that made me mad. Both were new to me & I didn’t like them & they didn’t like me. I told them if they put any down my throat I would throw up all over everything. (One of the Drs. is a Sheeny & one is a Wop). The Wop said, “your stomach is about 4 times as big as it should be.” I said all right, cut it open & take a chunk out. I suppose they thought I would say they could put those tubes down my throat & in my nose. Roy telephoned to find out if he could take me home.

Well this is the 16 so I just as well quit. Roy turns the TV on so loud I can’t write. I am feeling the best I have in a long time. They have given me so many shots. I think that may have helped my head aches, but I have a terrible roaring in it all the time it seems others can hear it.

When we first came to California, Feb was the finest month of the year. I can get in & out of the car with a little help but I can’t get up & down steps & that is why I can’t go to church. If the weather ever gets really good & all can get together on the time, we may get over to see you. We often talk of it.

Now remember no presents this year. There is nothing I want or need & I think most of us are in no physical or financial position to do so. And now good night with love.

God bless you & yours,

Your loving Mother, N.C.

Two weeks later, on January 2, 1956, Nellie Belle Chamberlin Chatfield died in her home. It took three times of administering the last rites to her to get her to go, and she was highly vexed that she didn’t die the first two times.

Jan 2, 1956: Death of Nellie Belle (Chamberlin) Chatfield (age 82), at her home on Boucher in Chico, Butte County, California. Her death certificate does not list her cause of death. She is buried in the Catholic Section of the Chico Cemetery in Chico, nowhere near her husband.

The C. on her headstone stood for Chamberlin, her maiden name. Her family didn’t know her middle name was Belle. No one did—she detested being called Nellie Belle.

Jul 20, 1956: Death of Leo Willard Chatfield (age 58), 2nd child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Camptonville, Yuba County, California; of a heart attack.

Aug 1, 1956: Marriage of Roy Elmer Chatfield and Josephine “Jo” Elizabeth Chambers,4th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Chico, Butte County, California.

Nov 9, 1978: Death of Noreen Ellen “Babe” (Chatfield) Clemens (age 53), my mother and 10th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Whittier, Los Angeles County, California of suicide.

Jul 11, 1978: Death of Roy Elmer Chatfield (age 77), 4th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Chico, Butte County, California; of heart failure.

Sep 26, 1978: Death of Verda Agnes (Chatfield) Day (age 70), 7th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Chico, Butte County, California; of heart failure.

Oct 3, 1981: Death of Arden Sherman Chatfield (age 71), 8th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Chico, Butte County, California; of heart failure.

Nov 21, 1983: Death of Nellie Mary “Nella May” (Chatfield) McElhiney (age 80), 5th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Martinez, Contra Costa County, California; of a stroke.

Aug 6, 1986: Death of Charles Joseph “Charley” Chatfield (age 90), 1st child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Paradise, Butte County, California; heart attack.

Feb 17, 1993: Death of Jacqueline “Ina” (Chatfield) Fouch (age 80), 9th child of Charles Chatfield & Nellie Chamberlin, in Yuba City, Sutter County, California; of old age and heart problems.